Keening Write

We must, as my ancestors would say, give the dead their due...

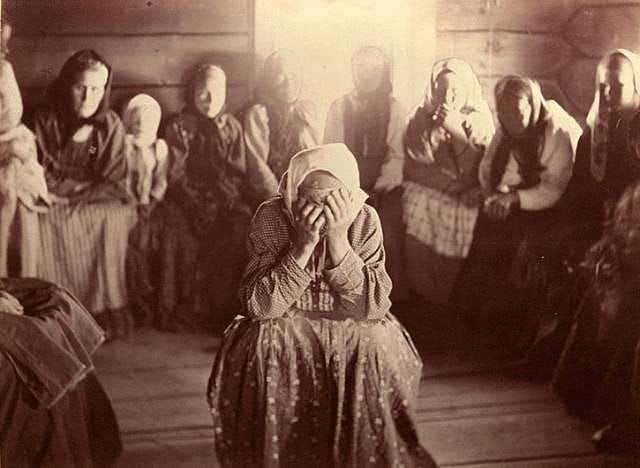

If you’ve ever heard Keening, you think little of story. It is not enough to say that it is ritual weeping. It would be truer to say it is the opening of a chasm into the deepest sufferings and sorrow of human beings, allowing the cacophony of wailing to distill itself through the bodies of a handful of women, each one made of the ashes from cold fire pits and the first leather tanned well before civilization began.

Keening is mostly gone from the Celtic world. For the Irish, the Keening Wake died out in the 1950’s under pressure of the Catholic Church and the forces of conformity that haunt indigenous communities with a history of colonial occupation. The rawness of Keening was too primitive and contrary to the formal way the Church addressed death. The roughness, darkness, and power of elder women to affect people must have chafed the leadership of the church mightily.

As was often the case among rural folk, it could take days for all the necessary people to arrive to properly address an important loss. The Keening tradition evolved out of that environment; agrarian, pre-industrial, indigenous. Keeners were the lead grievers of their community, usually elderly women who knew loss well. They were honored and valued for their ability to bring forth the depth of sorrow from even the most shut down person. Through singing the stories of their own losses, then inviting in deep weeping, they supported their communities for centuries.

Keening does entail storytelling, though you might not think it by just hearing the sounds arising from Keeners. According to Jude Lally @ Ancestral Mothers of Scotland & Gather the Keeners , a Scottish artist and teacher renewing the keening tradition in her own culture, keening is made up of three parts: salutation, verse, and cry. The first two parts are very much based in language; salutation describing the qualities and deeds of the deceased, and verse containing traditional themes and important words specific to the culture in urging the deceased to move on from life.

That part of the ritual is important because Keening does not just to draw the community together in its expression of grief over a loss, it also helps the spirit of the departed move on. This is echoed by Martine Prechtel, a shaman, writer, artist, and spiritual teacher in the Mayan tradition. The dead may never properly make their journey if they are not well grieved. People dig deep when grieving the dead in his culture, making sure those whom they love make it to the other side. Keening traditions draw on our collective humanity to birth our beloveds into the next world.

I wish I could say that grieving as Keeners do comes naturally to me – it does not. Fortunately, I have a daughter who has been my grief teacher. As with many young people, it took time for loss to sink in, for the reality of losing a mother to settle into her heart. It was late in the summer of her fifth year that grief finally caught up to her.

From my book, Wilder Grief, Discovering the Song of Life After Loss:

“‘I want Momma! I wish Momma was here! I MISS MOMMA!’

She screamed so loudly every window in the house shook. Her crying was deeper than I'd ever heard her cry. She wailed from the bottoms of her feet, through her heart and out the top of her head. She unleashed everything she had. I held her, which is the only thing I could do. Each scream tore through me, but I had nothing to offer. No fixes, no excuses…She had broken water. She knew how to grieve for Momma. She kept at it.”

For weeks her crying sessions were part of our nightly routine. She started crying after I tucked her in. Her older brother, ten at the time, would come into her room and wrap his lanky arms around both of us as I rocked her until she fell asleep, tears drying on her face. Her crying sessions eventually tapered off but they popped back up from time to time. Momma entered into her sobs when a beloved pet died, she was sick or just had a really bad day. I never tried to still her tears. Her wailing was such a powerful force of nature, it felt immoral to try to stifle it in any way.

True Keeners are born from the forge of life and loss. Who of us knows grief better than mothers who have lost the children they have birthed from their own bodies? From an interview, a woman who grew up in a village where keening was still alive : “we grew up being unafraid of the sound of grief,” she said, “not like it is today.” We prefer to make grief small in our modern world, we’re comfortable creating small spaces for it, where it will not interrupt our great dreams of success. Both of my kids have grown up unafraid of the sound of grief because of my daughters fierce, vulnerable, unbridled heart. Grief holds a large space in our lives, as does joy.

I think it’s fair to say writing can be a part of Keening, but writing itself is not Keening. We must, as my ancestors would say, give the dead their due. But there are ways that writing touches that place of Keening within me. It is not hard for me to feel the depth of the Keening wail, watching my two children grow up without their mother.

Mother Songs

I sing Mother songs every day,

while I cook his favorite dinner

and brush her hair at night,

watching the show she likes.

Her body relaxes

into the warmth

of a Mother

who is gone

but still has hands

that might stroke her hair

and make her feel like love never ends.

We secretly pass griefs thickness between us,

in whispers

about who's missing,

and what love might be

without her.

I hold them both,

pulling each into my heart

until the longing I feel

has eased

and the day has been enough.

Mother Songs reflects those many quiet moments, as a single widowed parent, when we feel the absence of our partner acutely, but have nobody to share our feelings with. Every task, every meal cooked, bath prepared, load of laundry folded, becomes part of the song of loss only sweetened by our devotion to our children.

And there are many such quiet moments I found myself in, alone in bed in the dark, feeling profoundly all that I have lost.

Holding Bird

I still hold my cherished bird

in hand

sitting up at night

remembering when she flew

straight into the sun.

Her beak was an unyielding lance

made for piercing,

not love.

She didn’t die wilting

but diving forward

into the next wave.

I hold her at night

remembering when she flew

straight into the sun.

I can imagine myself, sitting at her graveside, surrounded with my community singing this lament to her, reminding her of how much she is missed, and the understanding that I accept she is gone from our lives.

In the stories of Keening rituals I get a sense that every feeling could be held within the Keening. Our aspirational feelings of being reunited, our retelling of the greatest and worst qualities of our beloveds, even the hardest parts of how they died, all have a place in that song.

Writing has held that place for me, making a space where everything known and unknown about loss can find its Keening path in this world.

This is the third in a series of four pieces on writing and grief. All are linked below:

Cairnes - on how writing gives us inner landmarks that help us to navigate our grief.

Holy Offerings - on how writing is an offering to those who have passed on.

Keening Write - on how writing can touch that inner place of keening for the dead.

Transformative Arts - on how the arts heal us, bringing us back to the world after our grief journey.

My life journey has been largely directed by a trifecta of keening…for my twin sister Kate, for our cherished first daughter Krista, for my beloved husband…now experiencing grief as the most authentic fulfillment of love🫂💙🕊️